New Articles and Deep Thoughts

We tackle editor/reviewer recommendations and try our first poll question

As we wrap up the final week of 2024 here at Organization Science, we have some new articles to report, our first poll question, and some thoughts on how authors can think carefully about recommending senior editors and reviewers when submitting their papers at our journal. First let’s start with the polls!

Back in the Pleistocene era (2007), I joined a small (i.e., the founder and an engineer named Derek) Pittsburgh-based startup called CivicScience with a focus on disrupting political polling through widgets embedded in a platform of third-party websites. Back then, one respondent in a typical political poll cost about $50. Now even Substack has polling widgets, so why not use them to help all of us learn what people are thinking? Well, don’t answer that, but we hope you’ll participate, and also hope that Substack improves its Pleistocene-era polling widget. Right now we’ll be limited to five answers and one question, so please excuse the imperfect methods.-Lamar

New Articles-in-Advance

-Gordon Scott

Here are four forthcoming papers with authors covering four continents (5 if Texas is now its own continent) and topics ranging from scientific management to activism, gender on boards, and stigmatization of tobacco. We hope you’ll take a look and enjoy reading them. And as you can see, our initiative to reduce the number of rounds and total review time is really paying off. Three of them were submitted in 2022 and one in 2023. You’ll see these total review times continue to fall moving forward. Many thanks to the great reviewers, editors, and authors that made these acceptances happen.

Haram Seo

What drives firms to engage in activism? While existing research highlights the role of employee ideology in shaping corporate activism, the conditions under which firms are more likely to act on employee ideology remain underexplored. By utilizing firms’ philanthropic donations to advocacy groups as a novel channel for comprehensively tracking corporate activism, the study provides large-scale empirical evidence that firms’ activism aligned with their employees’ ideology often emerges in response to the activism of select competitors—specifically, ideological opponents that advocate stances contrary to their employees’ values. Such activism disrupts employees’ false consensus bias and heightens demand for counteraction, creating a temporal window during which firms can garner greater employee appreciation through activism.

Board Gender Diversity Reforms Around the World: The Impact on Corporate Innovation

Kun Tracy Wang, Lin Cui, Nathan Zhenghang Zhu, Aonan Sun

Prior studies have investigated the role of board gender diversity reforms in addressing gender inequality in corporate leadership, but their impact on firm outcomes remains unclear. Using a unique hand-collected dataset of global reforms and a quasi-experimental approach, the study finds that empowerment-driven reforms lead to stronger innovation outcomes than those focused solely on representation. Comply-or-explain reforms are more effective than rule-based reforms in empowering women on boards, resulting in greater innovation gains. The positive effects of these reforms are more pronounced in countries with higher baseline gender inequality and a larger pool of qualified female directors. This research sheds light on the importance of empowering female board members to realize the economic benefits of gender equality in corporate leadership.

Ana M. Aranda, Eero Vaara, Helen Etchanchu, Jonne Y. Guyt

This study examines how stigmatization develops in contested industries, focusing on the U.S. tobacco industry. It identifies three stages of the process—defining harm, assigning blame, and shaping norms—each marked by active debates and resistance. The research offers a model explaining how attention, stigma-building efforts, and resistance interact to shape public perceptions. The findings are valuable for policymakers, managers, and advocacy groups, providing insights into how discursive strategies influence industry practices and regulations. By highlighting the partial and contested nature of stigmatization, the study offers lessons for addressing stigma in other contentious industries such as fossil fuels or pharmaceuticals. This paper contributes to the understanding of how societal pressures can drive change in powerful industries.

Design-Based and Theory-Based Approaches to Strategic Decisions

Alfonso Gambardella, Danilo Messinese

How do we make decisions under uncertainty? Some rely on probabilities and logical evaluation (“theory-based”), while others believe in shaping outcomes through bold action (“design-based”). To explore these approaches, researchers conducted a randomized trial with entrepreneurs. The findings revealed that theory-based entrepreneurs were cautious, avoiding low-probability ventures and earning higher average revenues by steering clear of common pitfalls. Design-based entrepreneurs, on the other hand, persisted despite unfavorable odds, achieving success in highly innovative projects by taking bold, transformative actions. Both trained groups demonstrated greater decisiveness, committing more readily to ventures and needing less information than the control group. The study underscores that while theory-based reasoning helps avoid costly mistakes, a design-oriented mindset is vital for navigating highly uncertain and innovative challenges.

Recommending Reviewers and Editors: Why Bother?

-Lamar Pierce

It’s tempting after spending years preparing a paper for first submission to breeze through that page on ScholarOne where we ask you for recommended senior editors and reviewers. After all, the ScholarOne submission process seems to go on and on, which might also explain how many people check the ethics boxes without actually disclosing related papers. But don’t blow off the editor and reviewer recommendations—they’re important for both the senior editors and for you the authors. After all, don’t you want your work evaluated by scholars who will understand and appreciate the type of work the paper represents? The last thing you want is for a paper to go to scholars who don’t fundamentally value or understand your approach. Here at Org Science, we put a lot of effort into editor and reviewer selection because we too want papers evaluated by those who will best understand them. The most valuable time editors can spend is in choosing the right reviewers, and your recommendations help tremendously in expediting and improving that process. So let’s discuss how you as a submitting author should approach this.

Don’t leave the editor recommendations blank!

This can be annoying for deputy editors for a couple of reasons. First, you as authors should have the best sense of who should handle it, and we appreciate your recommendations even if we won’t use all of them. But in particular, if you recommend three senior editors, we will try to get you one of them so long as they aren’t at max capacity or on leave. This is an important reason to use all of your recommendation slots. It’s also hard as a deputy editor to not interpret blank recommendations as either: a)a lack of care, or b)a lack of understanding. These clearly aren’t always the reasons, but they do creep into our minds sometimes.

But the most important reason is get the paper in the hands of someone who fundamentally values the topic, setting, and empirical approach. We all have somewhat different preferences and beliefs about what is interesting and important enough to publish in a top journal, at least at the margin. So start with someone who’s interested in the type of work you do and has the expertise to evaluate it fairly and accurately. This is really what you should hope for—that the evaluation is fair and accurate. It’s tempting to strategize around who you think will be lenient or more likely to be nice to you, but having observed many many decisions, it’s rarely that way—at least at Organization Science. I spend a lot of time carefully choosing our editors, and a key characteristic is believing they will be evenhanded in their evaluations. No person is perfectly unbiased, but we look for folks who recognize that and work to not let it drive their decisions. “Bias” and “preference” are often used interchangeably in common language, but they’re not the same thing. We welcome different preferences, but work to minimize bias.

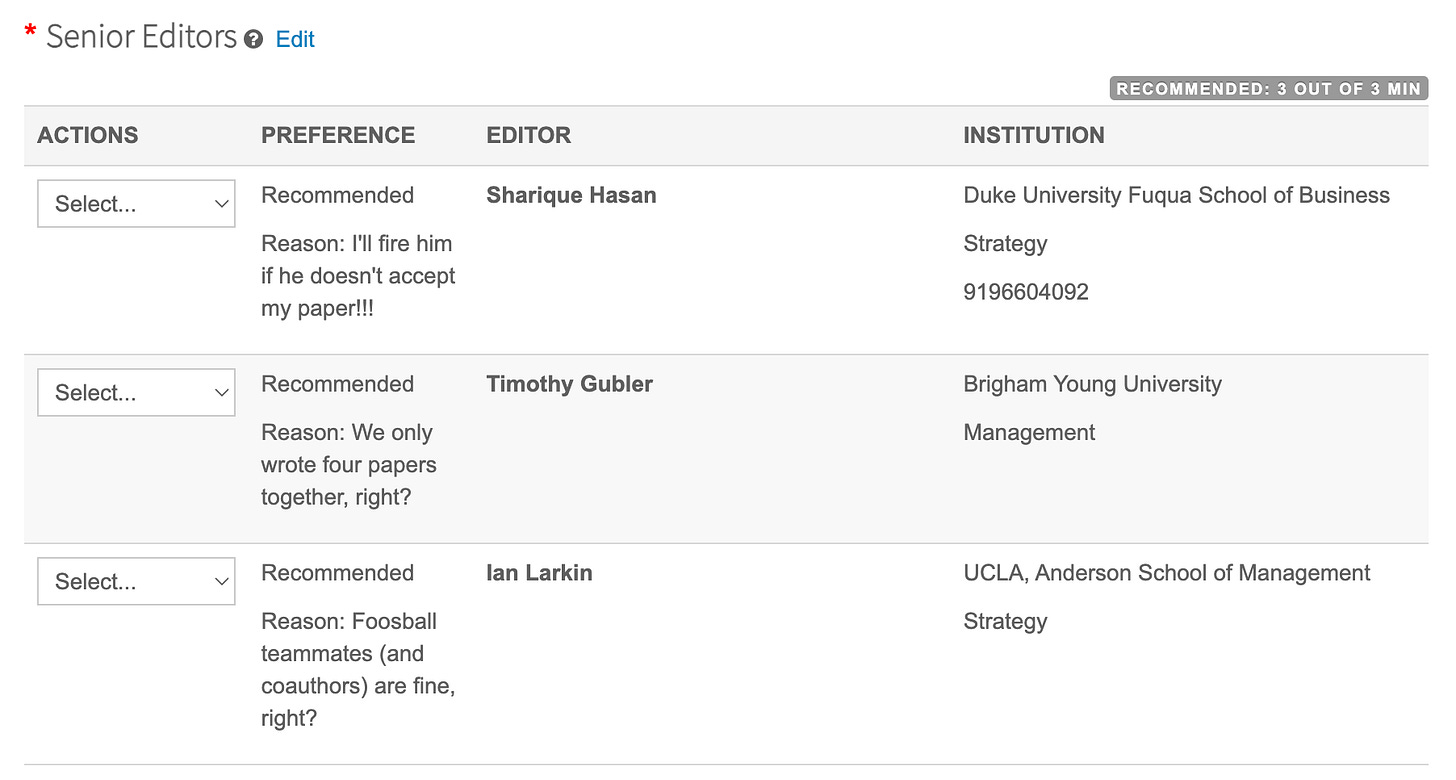

Don’t recommend editors or reviewers with conflicts of interest!

This should be obvious, but sometimes it’s evidently not, because we see this happen sometimes. Usually it’s because the submitting author doesn’t share the recommended list with their coauthors or bother to look carefully to see if the coauthors wrote a paper with the recommendee, work in the same institution, or anything else. The problem is that we as editors have to do that checking, because the cost of unwinding such a COI after Round 1 is high. So please check carefully when making your recommendations. It’s also a good idea not to recommend your close friends, lovers, or the drummer in your garage band, even if they don’t formally violate COI. We tend to notice this too, and it’s not a good start to the review process. There are plenty of great scholars out there to recommend as reviewers, and our editorial board has built-in redundancy to ensure the one editor that is a good fit isn’t conflicted out. When I was a junior scholar, submitting to Org Science was tricky because the only senior editor at the time who was an economist was my colleague Nick Argyres (fortunately lots of OT and OB folks have undergrad or masters degrees in econ). Today that would be very different at our journal, as it would be for a number of other fields and disciplines. You have a lot of good choices who aren’t conflicted, so use them.

Don’t recommend very senior famous people as reviewers (usually)

I know you’d love Daron Acemoglu, Alice Eagly, David Teece or Mark Granovetter to review your paper. But it is really unlikely to happen for a variety of reasons, even if they would love your paper. Now this isn’t always the case. We have a few folks at this level who review for us, but I’m not going to name them for obvious reasons. But most editors won’t even ask really high-profile folks because they know what the answer will be. Even if you ask people with many fewer (think order of magnitude) citations (like me), they likely have a ton of responsibilities. You can always recommend such people, but it can be a wasted slot. Now if they came up to you at your Org Science Winter Conference poster and told you it was the best paper they’ve ever seen, then go ahead. But recommend folks that you think would say yes. Junior and mid-career scholars are great options. So are research-active senior folks who do very closely related work. If you go through our ERB listing online, you’ll get great ideas. These folks only turn down review requests approximately 12% of the time, and it’s a really fantastic array of scholars.

Don’t recommend unqualified people as editors or reviewers

Editors weren’t born yesterday, and we read a lot into these recommendations. If someone recommends Lamar Pierce to review an ethnography of professional cricket teams, we’re going to get a bit suspicious. Sure, his review might be positive because he thinks a match only includes one team because everyone is wearing white. But a senior editor is going to catch that nincompoopery (as well has his predilection to make up words that don’t exist). An editor seeing such recommendations might arrive at the more innocuous explanation that the authors didn’t think carefully about their recommendations. But they might also arrive at the worse explanation—that you didn’t want true experts because they would immediately see your paper isn’t very good. Believe me, as editor I have seen a number of sets of recommendations where it was obvious that: a)the reviewer was not a great choice, and b)that the submitting author very well knew this.

Isn’t this column too negative for the holiday season?

Yes probably. But Santa’s failure to deliver me new bionic legs and a decent tenor voice has left me a bit grumpy.

Didn’t we learn from bond markets not to let people choose who evaluates them?

Well yes. I wrote a bunch of papers on that in emissions testing, as have others in safety inspection, bond ratings, and other settings. The reason this system works in journals is that the evaluator is blinded and the recommendation is not determinant. An editor evaluates recommendations and chooses zero, one, or even two. What might be surprising for junior scholars is that nearly every editor I’ve talked to reports that it’s the recommended reviewer that is the most negative. Why might that be? My theory is that these are frequently the real experts on a topic, setting, or method. Being that, they are the ones best qualified to identify serious problems or inaccuracies, but also great promise. But really, this is what we want in our research—to have experts who prevent us from publishing our deeply flawed work. I once emailed an Org Science senior editor (an OT person with an economics masters) who had rejected my paper, expressing gratitude for identifying serious flaws that justified rejection. I’d much rather say “oh $&@!, I did that completely wrong” after a rejection than after it came out in print.

This was a very long column. . . what did I learn?

Hopefully, you take away from this not only the importance of spending time providing thoughtful and ethical recommendations for senior editors and reviewers, but also some guidance for getting great feedback from the right review team—whether the decision is a revision request or rejection. There are far worse things than a well-reasoned and insightful rejection. You could get rejected by an editor who will question your attention to detail and even worse your ethics. Or perhaps even worse, you could publish a paper that is quickly and widely recognized as wrong. Sure, I’ve gotten pretty ticked off a number of times over rejections, and maybe even some of that frustration was justified. But with the trend toward greater research transparency, data availability, and replication, it is becoming increasing valuable to have your empirically incorrect papers rejected. Which is partly why you want to carefully select recommended editors and reviewers who will promote your paper if it shines and stop it if it’s simply wrong. I know it’s not that simple, but we should all want our work evaluated by those who are best qualified, even if that means the disappointment I’ve experienced many times before—the realization that your paper is not as strong as you had hoped or initially thought. Hopefully, with this disappointment will come the gratitude that the peer review process, as clunky and noisy as it can be, caught something seriously flawed.

What resources can help me recommend the right reviewers/editors?

One of the big concerns we discuss here at the journal is the unequal informational resources available to different scholars. I was always fortunate to have a strong network and colleagues to ask for advice, so if you have that privilege, definitely use it. But if you don’t, there are a lot of ways you can still gather this information. Which editors and authors are you citing, and more importantly, who has published work like this in the previous 3-5 years? Really, Google Scholar is amazing, and fifteen minutes doing detailed searches will give you a number of options. Whose recent work do you admire with the same setting/methods/theory/data type? If it was published in Org Science, even better! Which of these potential reviewers are on the ERB? What are editors currently studying in their own work? You have a ton of options for editors or ERB members at our journal, so unless you are doing something really unique, finding multiple options shouldn’t be hard.

We’re going to experiment with building a senior editor recommendation engine to try to level the playing field for folks without networks or mentoring. But mostly, I hope this column will serve some of that purpose in providing institutional knowledge about how to use the important tool of recommendation.

-Lamar

What you’ve written sounds interesting. I have two reasons for commenting: one I have a manuscript about the nine forms of power that can be used by a leader to motivate or control subordinates. It builds on the 1957 French and Raven five forms of power. My second reason is that I would like to be a reviewer for your journal.